If you’ve never seen the movie Analyze This, here’s the quick pitch: A member

of, let’s say, a New York family clan with questionable habits decides to

seriously considers therapy to improve his mental state. With Billy Crystal and

Robert De Niro driving the plot, hilarity is guaranteed. And while Analyze

This! satirically tackles issues of a caricatured MOB world, getting to the

root of problems with the right analytical tools is crucial everywhere. All the

more in a mission critical LOB-App world.

Enter the new WinForms Roslyn Analyzers, your domain-specific “counselor”

for WinForms applications. With .NET 9, we’re rolling out these analyzers to

help your code tackle its potential issues—whether it’s

buggy behavior, questionable patterns, or opportunities for improvement.

What Exactly is a Roslyn Analyzer?

Roslyn analyzers are a core part of the Roslyn compiler platform, seamlessly

working in the background to analyze your code as you write it. Chances are,

you’ve been using them for years without even realizing it. Many features in

Visual Studio, like code fixes, refactoring suggestions, and error diagnostics,

rely on or even just are Analyzers or CodeFixes to enhance your development

process. They’ve become such an integral part of modern development that we

often take them for granted as just “how things work”.

The coolest thing: This Roslyn based compiler platform is not a black box.

They provide an extremely rich API, and not only Microsoft’s Visual Studio IDE

or Compiler teams can create Analyzers. Everyone can. And that’s why WinForms

picked up on this technology to improve the WinForms coding experience.

It’s Just the Beginning — More to Come

With .NET 9 we’ve laid the foundational infrastructure for WinForms-specific

analyzers and introduced the first set of rules. These analyzers are designed

to address key areas like security, stability, and productivity. And while this

is just the start, we’re committed to expanding their scope in future releases,

with more rules and features on the horizon.

So, let’s take a real look of what we got with the first sets of Analyzers we’re

introducing for .NET 9:

Guidance for picking correct InvokeAsync Overloads

With .NET 9 we have introduced a series of new Async APIs for WinForms. This

blog

post

describes the new WinForms Async feature in detail. This is one of the first

areas where we felt that WinForms Analyzers can help a lot in preventing issues

with your Async code.

One challenge when working with the new Control.InvokeAsync API is selecting

the correct overload from the following options:

public async Task InvokeAsync(Action callback, CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

public async Task<T> InvokeAsync<T>(Func<T> callback, CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

public async Task InvokeAsync(Func<CancellationToken, ValueTask> callback, CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

public async Task<T> InvokeAsync<T>(Func<CancellationToken, ValueTask<T>> callback, CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)Each overload supports different combinations of synchronous and asynchronous

methods, with or without return values. The linked blog post provides

comprehensive background information on these APIs.

Selecting the wrong overload however can lead to unstable code paths in your

application. To mitigate this, we’ve implemented an analyzer to help developers

choose the most appropriate InvokeAsync overload for their specific use cases.

Here’s the potential issue: InvokeAsync can asynchronously invoke both

synchronous and asynchronous methods. For asynchronous methods, you might pass a

Func<Task>, and expect it to be awaited, but it will not. Func<T> is

exclusively for asynchronously invoking a synchronous called method – of which

Func<Task> is just an unfortunate special case.

So, in other words, the problem arises because InvokeAsync can accept any

Func<T>. But only Func<CancellationToken, ValueTask> is properly awaited by

the API. If you pass a Func<Task> without the correct signature—one that

doesn’t take a CancellationToken and return a ValueTask—it won’t be awaited.

This leads to a “fire-and-forget” scenario, where exceptions within the function

are not handled correctly. If such a function then later throws an exception, it

will may corrupt data or go so far as to even crash your entire application.

Take a look at the following scenario:

private async void StartButtonClick(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

_btnStartStopWatch.Text = _btnStartStopWatch.Text != "Stop" ? "Stop" : "Start";

await Task.Run(async () =>

{

while (true)

{

await this.InvokeAsync(UpdateUiAsync);

}

});

// ****

// The actual UI update method

// ****

async Task UpdateUiAsync()

{

_lblStopWatch.Text = $"{DateTime.Now:HH:mm:ss - fff}";

await Task.Delay(20);

}

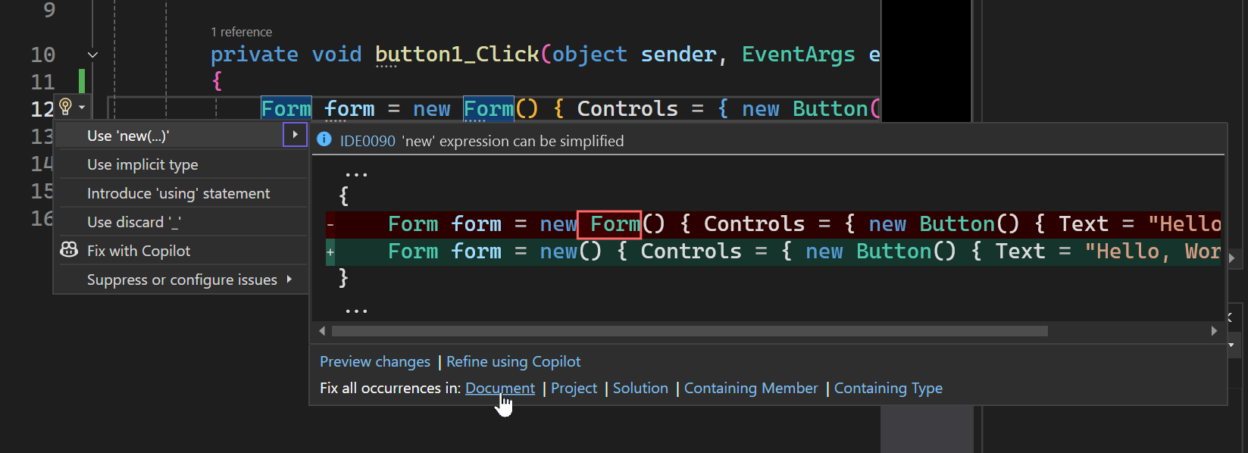

}This is a typical scenario, where the overload of InvokeAsync which is supposed

to just return something other than a task is accidentally used. But the

Analyzer is pointing that out:

So, being notified by this, it also becomes clear that we actually need to

introduce a cancellation token so we can gracefully end the running task, either

when the user clicks the button again or – which is more important – when the

Form actually gets closed. Otherwise, the Task would continue to run while the

Form gets disposed. And that would lead to a crash:

private async void ButtonClick(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

if (_stopWatchToken.CanBeCanceled)

{

_btnStartStopWatch.Text = "Start";

_stopWatchTokenSource.Cancel();

_stopWatchTokenSource.Dispose();

_stopWatchTokenSource = new CancellationTokenSource();

_stopWatchToken = CancellationToken.None;

return;

}

_stopWatchToken = _stopWatchTokenSource.Token;

_btnStartStopWatch.Text = "Stop";

await Task.Run(async () =>

{

while (true)

{

try

{

await this.InvokeAsync(UpdateUiAsync, _stopWatchToken);

}

catch (TaskCanceledException)

{

break;

}

}

});

// ****

// The actual UI update method

// ****

async ValueTask UpdateUiAsync(CancellationToken cancellation)

{

_lblStopWatch.Text = $"{DateTime.Now:HH:mm:ss - fff}";

await Task.Delay(20, cancellation);

}

}

protected override void OnFormClosing(FormClosingEventArgs e)

{

base.OnFormClosing(e);

_stopWatchTokenSource.Cancel();

}The analyzer addresses this by detecting incompatible usages of InvokeAsync and

guiding you to select the correct overload. This ensures stable, predictable

behavior and proper exception handling in your asynchronous code.

Preventing Leaks of Design-Time Business Data

When developing custom controls or business control logic classes derived from

UserControl, it’s common to manage its behavior and appearance using

properties. However, a common issue arises when these properties are

inadvertently set at design time. This typically happens because there is no

mechanism in place to guard against such conditions during the design phase.

If these properties are not properly configured to control their code serialization behavior, sensitive data set during design time may unintentionally leak into the generated code. Such leaks can result in:

- Sensitive data being exposed in source code, potentially published on platforms like GitHub.

- Design-time data being embedded into resource files, either because necessary

TypeConverters for the property type in question are missing, or when the form

is localized.

Both scenarios pose significant risks to the integrity and security of your

application.

Additionally, we aim to avoid resource serialization whenever possible. With

.NET 9, the Binary Formatter and related APIs have been phased

out

due to security and maintainability concerns. This makes it even more critical

to carefully control what data gets serialized and how.

The Binary Formatter was historically used to serialize objects, but it had

numerous security vulnerabilities that made it unsuitable for modern

applications. In .NET 9, we eliminated this serializer entirely to reduce attack

surfaces and improve the reliability of applications. Any reliance on resource

serialization has the potential to reintroduce these risks, so it is essential to adopt safer

practices.

To help you, the developer, address this issue, we’ve introduced a

WinForms-specific analyzer. This analyzer activates when all the following

mechanisms to control the CodeDOM serialization process for properties are

missing:

SerializationVisibilityAttribute: This attribute controls how (or if)

the CodeDOM serializers should serialize the content of a property.- The property is not read-only, as the CodeDOM serializer ignores

read-only properties by default. DefaultValueAttribute: This attribute defines the default value of a

property. If applied, the CodeDOM serializer only serializes the property

when the current value at design time differs from the default value.- A corresponding

private bool ShouldSerialize<PropertyName>()method is

not implemented. This method is called at design (serialization) time to

determine whether the property’s content should be serialized.

By ensuring at least one of these mechanisms is in place, you can avoid

unexpected serialization behavior and ensure that your properties are handled

correctly during the design-time CodeDOM serialization process.

But…this Analyzer broke my whole Solution!

So let’s say you’ve developed a domain-specific UserControl, like in the

screenshot above, in .NET 8. And now, you’re retargeting your project to .NET 9.

Well, obviously, at that moment, the analyzer kicks in, and you might see

something like this:

In contrast to the previously discussed Async Analyzer, this one has a Roslyn

CodeFix attached to it. If you want to address the issue by instructing the

CodeDOM serializer to unconditionally never serialize the property content,

you can use the CodeFix to make the necessary changes:

As you can see, you can even have them fixed in one go throughout the whole

document. In most cases, this is already the right thing to do: the analyzer

adds the SerializationVisibilityAttribute on top of each flagged property,

ensuring it won’t be serialized unintentionally, which is exactly what we want:

.

.

.

[DesignerSerializationVisibility(DesignerSerializationVisibility.Hidden)]

public string NameText

{

get => textBoxName.Text;

set => textBoxName.Text = value;

}

[DesignerSerializationVisibility(DesignerSerializationVisibility.Hidden)]

public string EmailText

{

get => textBoxEmail.Text;

set => textBoxEmail.Text = value;

}

[DesignerSerializationVisibility(DesignerSerializationVisibility.Hidden)]

public string PhoneText

{

get => textBoxPhone.Text;

set => textBoxPhone.Text = value;

}

.

.

.Copilot to the rescue!

There is an even more efficient way to handle necessary edit-amendments for

property attributes. The question you might want to ask yourself is: if there

are no attributes applied at all to control certain aspects of the property,

does it make sense to not only ensure proper serialization guidance but also to

apply other design-time attributes?

But then again, would the effort required be even greater—or would it?

Well, what if we utilize Copilot to amend all relevant property attributes

that are really useful at design-time, like the DescriptionAttribute or the

CategoryAttribute? Let’s give it a try, like this:

Depending on the language model you picked for Copilot, you should see a result

where we not only resolve the issues the analyzer pointed out, but Copilot also

takes care of adding the remaining attributes that make sense in the context.

Copilot shows you the code it wants to add, and you can merge the suggested

changes with just one mouse click.

And those kind of issues are surely not the only area where Copilot can assist

you bigtime in the effort to modernize your existing WinForms applications.

But if the analyzer flagged hundreds of issues throughout your entire solution,

don’t panic! There are more options to configure the severity of an analyzer at

the code file, project, or even solution level:

Suppressing Analyzers Based on Scope

Firstly, you have the option to suppress the analyzer(s) on different scopes:

- In Source: This option inserts a #pragma warning disable directive

directly in the source file around the flagged code. This approach is useful

for localized, one-off suppressions where the analyzer warning is unnecessary

or irrelevant. For example:

#pragma warning disable WFO1000

public string SomeProperty { get; set; }

#pragma warning restore WFO1000- In Suppression File: This adds the suppression to a file named

GlobalSuppressions.cs in your project. Suppressions in this file are scoped

globally to the assembly or namespace, making it a good choice for

larger-scale suppressions. For example:

[assembly: System.Diagnostics.CodeAnalysis.SuppressMessage(

"WinForms.Analyzers",

"WFO1000",

Justification = "This property is intentionally serialized.")]- In Source via Attribute: This applies a suppression attribute directly to

a specific code element, such as a class or property. It’s a good option when

you want the suppression to remain part of the source code documentation. For

example:

[System.Diagnostics.CodeAnalysis.SuppressMessage(

"WinForms.Analyzers",

"WFO1000",

Justification = "This property is handled manually.")]

public string SomeProperty { get; set; }Configuring Analyzer Severity in .editorconfig

To configure analyzer severity centrally for your project or solution, you can

use an .editorconfig file. This file allows you to define rules for specific

analyzers, including their severity levels, such as none, suggestion, warning,

or error. For example, to change the severity of the WFO1000 analyzer:

# Configure the severity for the WFO1000 analyzer

dotnet_diagnostic.WFO1000.severity = warningUsing .editorconfig Files for Directory-Specific Settings

One of the powerful features of .editorconfig files is their ability to control

settings for different parts of a solution. By placing .editorconfig files in

different directories within the solution, you can apply settings only to

specific projects, folders, or files. The configuration applies hierarchically,

meaning that settings in a child directory’s .editorconfig file can override

those in parent directories.

For example:

- Root-level .editorconfig: Place a general .editorconfig file at the

solution root to define default settings that apply to the entire solution. - Project-specific .editorconfig: Place another .editorconfig file in the

directory of a specific project to apply different rules for that project while

inheriting settings from the root. - Folder-specific .editorconfig: If certain folders (e.g., test projects,

legacy code) require unique settings, you can add an .editorconfig file to those

folders to override the inherited configuration.

/solution-root

├── .editorconfig (applies to all projects)

├── ProjectA/

│ ├── .editorconfig (overrides root settings for ProjectA)

│ └── CodeFile.cs

├── ProjectB/

│ ├── .editorconfig (specific to ProjectB)

│ └── CodeFile.cs

├── Shared/

│ ├── .editorconfig (applies to shared utilities)

│ └── Utility.csIn this layout, the .editorconfig at the root applies general settings to all

files in the solution. The .editorconfig inside ProjectA applies additional or

overriding rules specific to ProjectA. Similarly, ProjectB and Shared

directories can define their unique settings.

- Use Cases for Directory-Specific .editorconfig Files Test Projects:

Disable or lower the severity of certain analyzers for test projects, where some

rules may not be applicable.

# In TestProject/.editorconfig

dotnet_diagnostic.WFO1000.severity = none

Legacy Code: Suppress analyzers entirely or reduce their impact for legacy codebases to avoid unnecessary noise.# In LegacyCode/.editorconfig

dotnet_diagnostic.WFO1000.severity = suggestion

Experimental Features: Use more lenient settings for projects under active development while enforcing stricter rules for production-ready code.By strategically placing .editorconfig files, you gain fine-grained control over

the behavior of analyzers and coding conventions, making it easier to manage

large solutions with diverse requirements. Remember, the goal of this analyzer

is to guide you toward more secure and maintainable code, but it’s up to you to

decide the best pace and priority for addressing these issues in your project.

As you can see: An .editorconfig file or a thoughtfully put set of such files

provides a centralized and consistent way to manage analyzer behavior across

your project or team.

For more details, refer to the .editorconfig

documentation.

So, I have good ideas for WinForms Analyzers – can I contribute?

Absolutely! The WinForms team and the community are always looking for ideas to

improve the developer experience. If you have suggestions for new analyzers or

enhancements to existing ones, here’s how you can contribute:

- Open an issue: Head over to the WinForms GitHub

repository and open an issue describing

your idea. Be as detailed as possible, explaining the problem your analyzer

would solve and how it could work. - Join discussions: Engage with the WinForms community on GitHub or other

forums. Feedback from other developers can help refine your idea. - Contribute code: If you’re familiar with the .NET Roslyn analyzer

framework, consider implementing your idea and submitting a pull request to

the repository. The team actively reviews and merges community contributions. - Test and iterate: Before submitting your pull request, thoroughly test

your analyzer with real-world scenarios to ensure it works as intended and

doesn’t introduce false positives.

Contributing to the ecosystem not only helps others but also deepens your

understanding of WinForms development and the .NET platform.

Final Words

Analyzers are powerful tools that help developers write better, more reliable,

and secure code. While they can initially seem intrusive—especially when they

flag many issues—they serve as a safety net, guiding you to avoid common

pitfalls and adopt best practices.

The new WinForms-specific analyzers are part of our ongoing effort to modernize

and secure the platform while maintaining its simplicity and ease of use.

Whether you’re working on legacy applications or building new ones, these tools

aim to make your development experience smoother.

If you encounter issues or have ideas for improvement, we’d love to hear from

you! WinForms has thrived for decades because of its passionate and dedicated

community, and your contributions ensure it continues to evolve and remain

relevant in today’s development landscape.

Happy coding!

The post WinForms: Analyze This (Me in Visual Basic) appeared first on .NET Blog.